IX. A conversation with an archive manager, part 1: On fees for wearing a “Jewish outfit”

2023/04/13

Text: Magdalena Krysińska-Kałużna, March 2023

It has been nearly a year since the publication of the previous episode. I am collecting information once again to then put it together like pieces of a puzzle in an attempt to recreate the prewar world of Konin’s Jews. This time in my search I turn to the manager of the Konin’s department of the National Archive in Poznan, Mr. Piotr Rybczynski. I tell him about the project and show the map of prewar Konin created and printed out in spring last year.

‘You know and I know what this is supposed to mean, but if someone else looks at this map and reads “rabbi’s house”, they will think that it was continually inhabited by one rabbbi or another and that maybe it was owned by a rabbi, too. Yet, only the last rabbi lived here and it wasn’t his property either’ says Mr. Rybczynski and I must agree.

‘We’ll change the caption in the online version’ I promise. ‘The war in Ukraine began almost concurrently with this project and I found myself having much less time to work on the map. Only one month and a half’ I attempt to justify myself and the inaccurate description.

‘Only several buildings belonged to the synagogue district (in the years before the World War 2 it was referred to as a “district”, no longer a “community”). They were: the Great Synagogue, the Talmudic House, the Mikvah and the shochet’s house’ enumerates Mr. Rybczynski. ‘At the same time, it’s not certain that the shochet always lived in that house.’

‘And the school?’ I ask.

‘The school was constructed quite late. The building, dating back to early 20th century, didn’t belong to the Jewish community as much as it did to the citizenry in general. Its status was similar to that of Zemelka’s House. You see, in 19th century there was a distinction between the property of the city coffers and the property of the citizens. Only later these two concepts merged into one. This was the case with the building constructed from the propination funds, destined to be an elementary school and which today is a parish building.’

‘Were Jews allowed to use the propination tax?’

‘Not until 1862.* Jews, or more specifically: followers of Judaism, were limited by certain formal and legal regulations. As a result of the January Uprising, a number of reforms was put in place. The legal order dating back to the Middle Ages, a part of which the propination tax was, ceased to exist in its old form.

‘But tenders were still organized until 1914. For instance, a tender for supplying lighting. Offer the best pricing terms while guaranteeing that the lighting – first oil-based, then kerosene-based – would work in the city and you’re the winner. Even before the equality of rights was introduced, Jews had participated in such tenders.’

I’m listening and I think to myself that the unfairness with which Polish peasants (emancipated only in 1861) were treated has been delineated to our society quite well. Meanwhile, the fact that a social group as big as that of Polish Jews did not possess same rights as Christians until 1860s is not common knowledge.

In the Kingdom of Poland, law was based on the constitution established by Tsar Alexander I which treated Christians and followers of Judaism differently. One of the limitations placed on Jews after 1815 was a prescription to reside only in specified precincts. The restrictions applied to physical movement and social mobility. I’m asking about the practical consequences of this regulation for the Jews of Konin.

‘Konin’s Jewish precinct, determined in the regulatory plan, consisted mostly of Żydowska Street and the present-day Zamkowy Square. However, having paid a fee, one could potentially receive an allowance to live outside the precinct’ explains the manager of the Konin’s archive.

‘The traditional precinct area was still recognized in the second half of the 19th century, even though it did not exist in the formal and legal sense anymore. But this is not to say that only Jews lived in the Jewish precinct. A townhouse owned by a Jew could be inhabited by all sorts of people, for instance: soldiers sent by the housing committee.

‘Another restriction which applied to Jews, also in Konin, was the fee for wearing a “Jewish outfit”. This was meant in the sense of Hasidic clothing. One Konin’s characteristic features was its significant Hasidic population. It was primarily them who shaped the image of the Jewish Konin. Also in the eyes of Jews themselves.

‘You need to remember that the population of religious Jews was not a monolith. They varied between each other. And sometimes, they argued. Especially in such small towns like Konin. This was a lively, dynamic community.’

‘Is it known how many Jews lived in Konin before the war?’

‘It was estimated that there were around 2,400. When it comes to the Jewish population, it was believed that faith determined ethnicity. It was assumed that there were hardly any converts to Judaism. If there was a change of denomination, it would have been in the opposite direction and it usually entailed ostracism and exclusion from the family of the baptised.

‘There was a bit of a mix-up in the 1921 census which brought about quite comic results. Throughout the country they would write things like “local” or “native”. In effect, it’s quite difficult to determine the actual size of the Jewish population of that time. Following 1918, the area underwent substantial changes. This affected everyone, but Jews in particular.

‘The whole 100-years-old economic model was based on the proximity to the border. The disappearance of this border was a critical hit for the archaic economy of Konin. Furthermore, it shrunk the number of Jewish residents in the town.’

TBC

*In 1862, an emancipatory act was issued within the Kingdom of Poland by margrave Aleksander Wielkopolski. It lifted most of the legal restrictions, which had previously limited Jews’ freedoms, leading to practical emancipation of the Jewish population.

Translation: Ada Kałużna

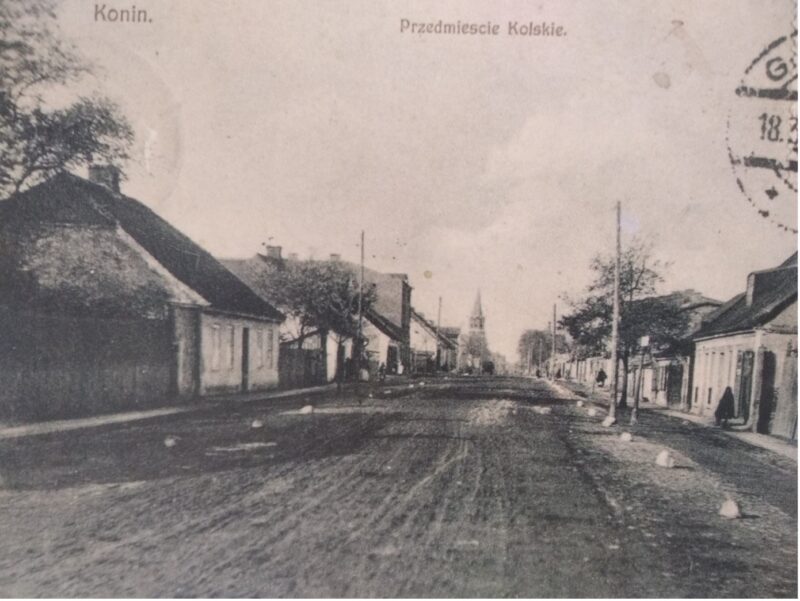

Przedmieście Kolskie (the Kolskie Suburbs) in Konin. The photo was taken between 1914 and 1920 by M. Pęcherski.