XI. Julian Joel, Konin’s Judym

2023/04/28

written by Magdalena Krysińska-Kałużna, April 2023

translated by Ada Kałużna

According to Wincenty Grętkiewicz, Konin hospital on Kolska Street run by Russian regional authorities accepted only very sick people.“[At the beginning of the 20th century,] Konin’s residents were in terrible health; it was largely caused by the contemporaneous climate conditions in the city. Consumption, an incurable illness back then, was wreaking havoc among children in many families.”*

As Theo Richmond, the author of Uporczywe echo, reminisces, his grandmother, born and raised in Konin, as well as hislong-lived mother did not pay particular attention to what the doctor had prescribed. They preferred cabbage compresses. Both of them were “extraordinarily resilient and had a heroic-level ability to accept sickness and pain”**. According to Richmond, this was related to the (lack of) availability of medical doctors in Konin at the beginning of the 20th century and to the high cost of medical treatment.

Following the World War I, the number of doctors in Konin grew. Among them were the past students of the Jewish junior high school: Izydor Kawa and Feliks Bułka. The two are believed to be the root source of the saying – oft repeated to sick patients – “you need some coffee (Polish: kawa) and a bread roll (Polish: bułka)”.

Another practitioner of the era was Julian Joel, who stated that “he would never even consider accepting pay for visiting a poor man’s home”***.

‘The economic situation of Konin’s residents before the World War II was more less the same for everyone. There were poor and rich people among Jews and non-Jews’ comments the manager of Konin’s division of the National Archives in Poznań, Piotr Rybczyński.

‘Joel was a unique personality and an unusual case which dismantled the cliches functioning within the Catholic community of the interwar period. Julian Joel was a doctor. He was born in Konin. He died at a very young age. I’m not sure if he went to the Jewish junior high, although some information seems to confirm it. He certainly did not pass his matura exam there.

‘He came from an affluent merchant family. His father, Herman Joel, was an equally interesting character. This was a family which – continuing to follow Judaism – defined itself as both Polish and Jewish. In Julian’s case, and in a large extent in Herman’s case as well, no one questioned this self-definition. Neither Poles, nor Jews.

‘Joel studied medicine. He was still a student when he enlisted to fight in the war of 1920 (the Polish-Soviet War). He was awarded the Cross of Valour for his involvement. After the war ended, Julian completed his medical education, moved to Konin and started working as a doctor in the so-called Sickness Fund.

‘The building from which this “district insurance company” operated was located on Mickiewicza Street. He worked there, but you could find him all over the place. Besides being a doctor and a reserve officer, he was also a member of the Voluntary Fire Brigade (referred to as the Fire Guard until 1928).

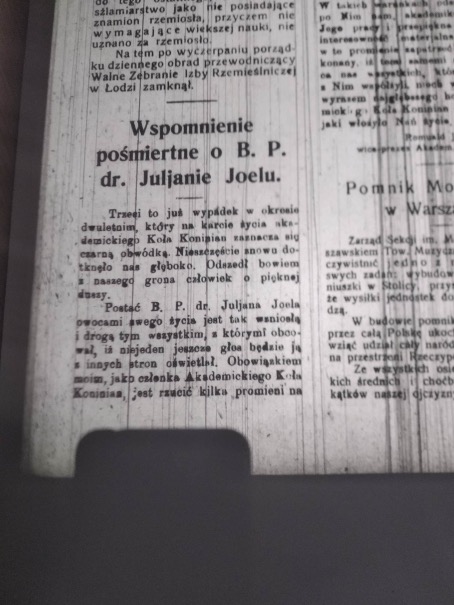

‘He died in 1930 and it was a big event for the whole town. It was not everyday that a person’s death was honored with an article in Głos Koniński (The Voice of Konin). Joel’s funeral made history and was a talking point for a long time afterwards.’

‘One of the most memorable Jewish funerals in Konin took place after doctor Joel’s death in the early 30s. The practitioner conquered the hearts of both Jewish and non-Jewish patients’ writes Richmond. ‘All stores were closed for the time of the funeral, attended by local dignitaries. A long cavalcade of Christians and Jews walked the streets of Konin to commemorate the dedicated and compassionate doctor.

‘He got appendicitis and, be it because he doubted his colleagues’ abilities or because it would provide him with more surgical experience, he decided to operate on himself. The experiment failed.’****

‘They would say about Joel afterwards that he was Konin’s Judym’ says Mr. Rybczyński. ‘In the Sickness Fund, patients didn’t pay for their visits and Joel allegedly even paid out of his own pocket to help them afford their medicine.

‘His father, Herman, would break down, believing his son would not achieve anything in life, but he himself was an interesting, socially involved character. In 1920, he joined the District Committee of National Defense as a treasurer. Joel never changed his denomination and Jews never questioned his Jewishness, while Poles – to simplify it – never questioned his Polishness and patriotism.’

Sitting in the archive and listening about Julian Joel, without remembering his story as described in Richmond’s book, I started feeling sympathetic and afraid. I was afraid to hear what happened to Joel during the war. I felt relieved hearing that he didn’t live to see it.

* Wincenty Grętkiewicz, Wspomnienia konińskie z lat mojej młodości. Konin, 2021, pp. 77.

** Theo Richmond, Uporczywe Echo. Sztetl Konin. Poszukiwanie. Media Rodzina, Poznań, 2001, pp. 204-5.

*** Michał Moszkowicz as cited by Theo Richmond in Konińska Księga Pamięci. (M. Gelbart, Ed.) Association of Konin Jews in Israel, Tel Awiw, 1968, pp. 414-5.

**** Theo Richmond, Uporczywe Echo. Sztetl Konin. Poszukiwanie. Media Rodzina, Poznań, 2001, pp. 222.

Below, you can see fragments of Głos Koniński newspaper from April 26th and May 3rd 1930 (microfilm photographs).